“I love the way you look at eucalyptus trees.” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, you look like you are in a daze. You seem to be looking at more than a tree.”

“There’s something about them,” I replied, “that fascinates me, is mysterious to me. I have always liked to watch them blow, especcially the manna gums because they are billowy. They are neat in the rain going back and forth with water falling past them. But when the storm is over and fog sets in a few days later, the grayness of their leaves and the denseness of the blue gums depress me. I go from being exhilarated in a storm to being frightened in the fog. The motion of the storm makes me excited to be alive, to think of the future with confidence as I venture into the park with my umbrella, smiling as I look to the trees. In the fog the stillness gives me the heebee jeebees. Between the eerie fog and the looming trees and stillness, a lot of thoughts come to me that scare me. I don’t think of the future and how great it will be. I think of my weaknesses and fears, realizing I am not and will never be who and what I want to be.

“Tell me more about the way I look.”

“You look like you are glad they are here,” he said. “Almost everybody likes trees because they are pretty or they give shade. You look at them like you have a relationship with them. Almost like they are you or you are them.”

“I still get excited in the rain and scared in the fog,” I told him. “But some changes happened. I remember when I first saw aboriginal art or imitations of aboriginal art. Trees were made to have muscularity and sexuality. The term the crotch of the tree took on new meaning. When I’d see lush grass growing in the crotch of trees in winter and spring, especially American elms on T Street – the ones with the erotic twist – I’d laugh and shake my head.

“Where I used to see prettiness and bleakness, I saw power and sensuality. It doesn’t matter the time of year. Their power and sensuality is my even keel. I get less excited in the rain and less depressed in fog.

“A lot of trees are sensuous and look powerful, but the trunks of the eucalyptus, the way they twist and erupt from the ground are more powerful looking than others.

“This is an age when hardly anyone has power,” I continued, “yet we hear a lot of talk about feeling empowered. When I see the trunks of eucalyptus, especially the blue gums and mannas that were planted in the old days, I think of power, power, power. Not political power or ego power, but natural power I seldom let surge forth like I see surging through eucalyptus.

“That’s what I want – to feel naturally powerful and sensuous, to live my power and sensuality. We’re encouraged to be gaudy or plastic with our sexuality, not real or genuine with it.

“Remember the movie about the woman who played the piano who went to New Zealand to get married?”

He nodded.

“Remember when the white kids are playing on the eucalyptus stumps with the aboriginal kids? All the kids are humping them. The aboriginal parents are laughing as they watch their kids get sexual with the trees. The white guy gets angry seeing the white kids humping trees, so he makes them stop.

“Trees serve many purposes. That could be one of them for us, but we are afraid.”

“Wow,” he said.

“Yeah. It’s a great way for kids to get comfortable with their body and one another. I wish I had grown up like that.”

“Trees have brought up all your stuff. Haven’t they?” he said. “And not just in winter.”

“You’re right,” I admitted. “I love it. It’s not that the pain feels good. It’s that the trees bring up thoughts and feelings about myself and community, power and sex and relationships that give my life meaning and hope – that I will rise like a big rod of a eucalyptus, shedding my bark so my fear to be free gives way to my fear of what will happen if I don’t become free, especially as I get older.

“It’s interesting,” I said.

“What is?”

“These trees that are sexual and sensuous to me arrived in California in the 1850s. That was during the first third of the Victorian era, the era where people wore a lot of uncomfortable clothes and seldom expressed how they felt.

“We planted a lot of eucalyptus here in Sacramento to drain our standing water so there would not be as many mosquitos. People also thought trees would purify the air to protect us from malaria. Malaria means bad air in Italian.

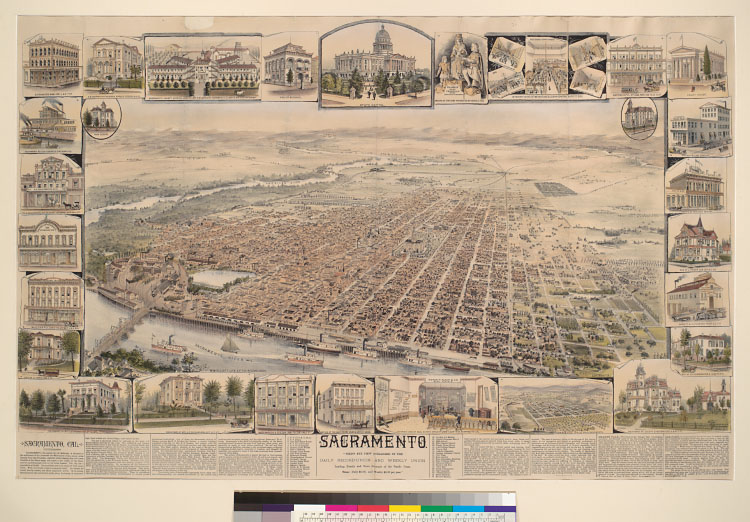

“In 1877 during the heyday of the Victorian era, Sacramento planted 4000 eyucalyptus trees. That’s a lot of one species, especially in those days when our city was not big and we didn’t have gasoline powered augers to dig holes.

“It’s also interesting that at this time more and more elms were being planted. Elms would become our most loved tree, our unofficial tree, our connection to prestige and old school political power. They would be our major claim to be the City of Trees.

“It’s too bad nobody was moved by the unkemptness of the eucalyptus, their hanging foliage and long strips of peeling bar, to start a campaign to dress more loosely, to bare one’s body and soul, to erupt with genuine passion.

“They must have done for somebody then what they do for me. But they would not have been able to talk about it like I am. They could not tell people or write that trees make them horny and dying to talk about things they never talked about before – that society has everything backwards.

“It’s interesting that eucalyptus are so expressive, but their name comes from a word which means to conceal. Their seeds are concealed in a capsule. Just like our passion is bottled up.

“It’s interesting too, that the Victorian Age, as much as it created beautiful things, was a secretive age. Their art was stately and had character, but it was not expressive or seductive. At least seduction will let you in on the secret.

“That’s what is great about eucalyptus. They are expressive and seductive. I cannot think of anything as expressive as a eucalyptus tree, or so mysterious. They make me want to participate in the mystery, but I can only participate if I express. I want to express so bad because I want to participate in the mystery so bad.”

“You want to be seduced,” he said.

“Yes,” I replied. “It isn’t that I’m not assertive or aggressive. I will be more expressive and sensuous, mysterious and seductive, if I find something greater than me or you to be seduced by. It is a freedom we don’t cultivate or understand as a society.

“You’re probably thinking why I sound desperate and not free as I talk about something I love more than anything. The more I’m passionate about trees and their mystery and my expressiveness, the more I realize I’m not supposed to express sensuality or concentrate on pursuing and expressing what give my life meaning.

“It’s only partly that we aren’t supposed to say what we mean or express who we are or what we love. The greater part is that we’re supposed to be enthusiastic about an image based mainly upon money. We aren’t supposed to say what we mean, but just appear to mean something we don’t.

“Trees are freely expressing themselves. We feel we’ve gotten away with something by not revealing who we are. It’s the freedom to – freedom from controversey. Trees in the old days gave us freedom from the sun, but they didn’t make us feel free to relax and express ourselves, to shine like the sun for each other to marvel at and be warmed by.

“It’s too bad we don’t feel an affection for each other to match the love we feel for our trees. Wouldn’t it be great if the best thing about the City of Trees was the dialogues we had with each other in the shade of trees in the parking lot after work and while we planted trees together at parks and schools? At home we would look forward to talking over family business and intimacies under our trees.

“The reason trees are pretty much just something pretty and not a source of passion, conviction or intensity is because we’ve not only bottled up our passion; we’ve put our passion into false gods like money, career, property and image instead of into trees and other natural stuff.

“Our passion is our secret. We don’t know it’s there. When I see the eucalyptus trees twisting up from the ground I feel my passion bubbling, overflowing.”

“It sounds like you know it’s there,” he said, “but you don’t know what to do with it.”

“I don’t know how to express it,” I replied. “I was always told trees are just trees. They may be pretty, but they are still just trees. It’s difficult to express how I feel. It’s almost sacrilegious to.

“I think of the movie again, how the aboriginal kids were probably better able to express themselves and feel comfortable with themselves than the white kids. Think of how humuliated the white kids were. They’d never act spontaneously again. They’d fear to be laughed at if they were in a group, or punished. If they were alone they’d feel guilty about humping a tree or taking off their clothes in the forest. When they’d get home they wouldn’t tell nobody nothin’ or they’d lie if asked.”

He looked at me.

“We’re out of sync,” he said.

“I want to be in sync,” I said. “Eucalyptus became our unofficial state tree not because of our love for their beauty, but because people loooked upon them as a cash crop. It’s almost like the more we planted them to make money, the more out of sync we became. The faster and crazier and stiffer our movement, the less motion anmd fluidity and magic we saw in trees. I can tell I’m in synch the more I value trees for their expressiveness and sensuality, their power and vulnerability and sense of movement, then try to incorporate all of those into me, even though I feel awkward.

“They were planted all over – on eucalyptus farms, as property lines, as windbreaks, along train tracks. I have a theory about eucalyptus along train tracks.”

I looked at him.

“Go on ,” he said.

“Trains got rolling at the same time eucalyptus trees did. That was the 1860s. More trains came. More people came. More eucalyptus were planted for fuel for the trains and lumber to build with. But eucalyptus here didn’t work out as a building material. It wasn’t very good as fuel for trains. Eucalyptus weren’t planted as much after about 1910, but their groves remained. Trains didn’t go away either.

“I said a minute ago that our society became faster and crazier and more cumbersome in our movement at the same time we were planting more eucalyptus. Trains are a great symbol for the increased pace, the increased competition and the use of our bodies to work ourselves to death, at least spiritual death.”

“I think trains are neat,” he said.

“Me too,” I said.

“But there’s something about trains,” I continued, “that attracted people more than eucalyptus trees. People liked eucalyptus for their shade but not their sensuousness or twist or sense of motion. The trains though, were different. Trains made a lot of people money and were appreciated for that. Trains made an even greater number of people bitter. Trains broke farmers, railroad employees and helped break agricultural workers. All these broke bitter people had stiff bodies that hurt. Yet almost everybody agreed that trains sounded beautiful in the dark. There weren’t street lights in those days and people spent a lot more time outside.

“They’d listen, either living the moment as they looked to the stars or feeling in their stiff, broken, bitter, relatively young body that they’d overcome the pain and help their kids become successes. People without kids would look to the sky thanking their lucky star they didn’t have someone else to take care of. They’d wonder how long they’d hold up.

“People were mesmerized and soothed by the motion and sound and rhythm. It got them back in sync, at least as long as the trains passed, and especially at night when they run the most trains. I imagine couples would lie in bed too sore, pissed off and afraid to sleep, then snuggle for comfort when they heard a train.

“There’s the other side of trains too. When you’re outside and it rumbles by, a lot of passion rushes forth with it. You scream knowing you are going places and are going to thunder and be awesome. ‘ Yeah!’ ‘Yeah!’ ‘Yeah!’ I’ve screamed it so many times.

“You too?” I asked.

He nodded.

“They’re both about passion” I said.

“The lullaby and intensity?” he asked.

“That too,” I said. “I meant trains and eucalyptus. Trains were a romantic passion for me, a youthful passion. The passion I feel watching eucalyptus isn’t about me going places, but about expressing myself wherever I go or end up. Trains helped me get my rhythm. Eucalyptus challenge me to let myself loose.

“There’s a lot of places in the state where eucalyptus grow along the railroad tracks. I’m thinking of the peninsula and Watsonville. There’s a lot on the Amtrak runs between here and Emeryville”

“How about here?” he asked.

“Along Elvas, behind Hughes Stadium, at Sac State,” I said. “Sac State is a great place for trains. The echo is unbelievable. I loved to watch the gray engines come lurking out of the fog behind the gray eucalyptus. The problem is that a lot of the trees are being cut. In a few years they might be gone. There are replacement trees that will get just as big, but they won’t have the mystery.”

“Why are they being removed?” he asked.

“Either they’re too old or they died in the freeze in the early nineties. Maybe because they are so big and break so easy, they are considered too dangerous. The drought could have weakened them or killed them and made them vulnerable to borers. A lot of people don’t like the shedded bark from eucalyptus. Maybe the old big trees have so much litter, they just had to go.”

“Tell me about the borers,” he said.

“Well, one of the things eucalyptus lovers have liked about eucalyptus is that they are free from pests. That was pretty much true until the weather change of the 1970s. There were a lot of drought years in the seventies and eighties. Even though eucalyptus have done well in California because they are drought resistant, rain in winter is important.

“With so many years of drought, the sap – the gum – stops to flow because there is not enough water in the ground for the entire root system to produce the gum to flow to the trunk and branches. The borer takes advantage of this.

“A healty tree produces gum which prevents the borer from penetrating. The borer lays its eggs where the bark has stripped away on blue gums and mannas. So when drought comes and the trees become weak, borers have a field day. Scientists say you can hear them crunch the wood.

“It’s funny to think that eucalyptus were planted in Sacramento to drain our bogs, but we also wanted them because they would be drought resistant every summer after the bogs were drained.

“What isn’t funny is the double whammy of the freezes and droughts. Lots of damaged wood. It is a fire hazard. Remember that fire in the Oakland hills?”

He nodded.

“A lot of people who hated eucalyptus trees found an excuse with the fires to try to get eucalyptus removed and different trees planted. These people think eucalyptus are ugly and the bark a nuisance.

“Fortunately there were a couple of groups that came to the rescue of eucalyuptus. One of them was down the highway in Davis. It was called the Eucalyptus Improvement Association. Another was called POET. It means Preserve Our Eucalyptus Trees. I love the acronym because eucalyptus are poetic.

“What bothers me about people who want to destroy the eucalyptus trees is that they want them destroyed even if the trees are healthy. There are eucalyptus that don’t shed bark like the blue gum and manna do. There is a wasp that can kill the borer. Eucalyptus look pretty much the same, so even if they were healthy and did not litter, people would want them cut because they don’t like them.

“Have you ever seen a eucalyptus that grew back after it’s been cut?

“I don’t know,” he said.

“There’s some great ones growing on the south side of Land Park across from the golf course. There’s a couple of picnic tables there. You can tell the trees were cut by several trunks growing next to each other. They are beautiful.

“People who want eucalyptus cut would have to have the stumps of the healthy ones yanked out of the ground. Think of the mud slides that would happen without roots in the ground. If they don’t do that, then they’d drill holes in the stumps and pour poison in the holes.”

I stopped.

“What do you think?”

“Now I know why you have the look you do,” he said. “You struggle with yourself, but you are lucky. If the people who don’t like eucalyptus trees had them chopped down, you’d marvel at the weeds coming up in the cracks of the stumps.”

Copyright © 2025 by David Vaszko

You must be logged in to post a comment.